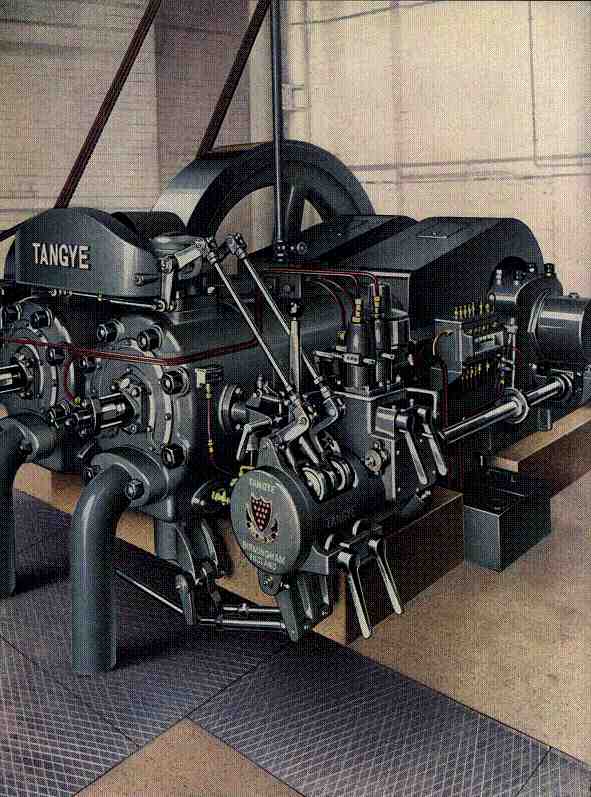

A Hundred Years of Engineering Craftsmanship 1857 - 1957

SELLING TO THE WORLD

THE firm which employed two workpeople in 1858 was employing 8oo by the end of

the ‘sixties, and within another twenty years had increased the number on its

payroll to 2,000. Such continued rapid expansion could scarcely have been

maintained without constant and careful attention to markets. James and Joseph,

helped by George especially in works management, had produced excellent

machines: Richard enthusiastically devoted himself to selling them. Competition

was always growing but Richard’s power of swift decision — sometimes apparently

ruthless — was of considerable advantage in his chosen field. Each aspect of

the brothers’ work was, in fact, complementary, although they themselves in the

heat of the day sometimes found difficulty in appreciating each other’s

talents.

Without much of the paraphernalia of twentieth century business efficiency -

telephones, typewriters and so on, advertising media, air travel - modern

salesmanship was only in embryo a century ago. But Richard possessed a gift for

publicity which made people remember the name of Tangye. ‘We launched the Great

Eastern, the Great Eastern launched us’ was particularly successful. Some

twenty years later he used the erection of Cleopatra’s Needle on the Embankment

for another simple, but telling, advertisement:

‘A.D. 1586 Fontana

raised the Obelisk in Rome

with 40 capstans, worked

by 960 men and 75 horses.

A.D. 1836 Le Bas raised the Luxor Obelisk in Paris with 20 capstans,

worked by 480 men.

A.D. 1878 Mr. John Dixon raised Cleopatra’s Needle in London, using four of Tangye’s.Patent

Hydraulic Lifting Jacks, worked by 4 men.’

An

easy appreciation of novel ideas, amounting perhaps on occasion to

over-enthusiasm, was also an invaluable asset in nineteenth century commerce.

It was this characteristic which doubtless caused Richard to concentrate so

much effort in Australasia and South Africa, but it also reveals itself in

smaller ways as, for example, in a letter to Joseph in November 1876: ‘I write

this with the new American “Type-writer” and can write faster than with pen and

ink, and with not a tenth of the fatigue’.

The structure of the selling organization which the firm built up was not, however,

essentially different from that of today. The first step was to establish

agencies at home and abroad, followed where possible by branch houses. Richard

Tangye’s heroes were Cobden and Bright, with their belief in world-wide free

trade, and throughout his life his trading policies actively endorsed his

political principles.

HOME TRADE

By the time of the 1862 Exhibition Tangyes had already built up friendly

relations with two London merchants. S. & E. Ransome of Essex

Street, Strand,

acted as sole agents for Weston’s pulley blocks. From the first they undertook

responsibility for this trade and continued to develop it, sending travellers

at their own expense throughout Great Britain as well as abroad. Their exclusive

agency continued not only for the duration of the original patent but was later

extended for the period of a new patent which covered an improved block. The

sole agent for all other machinery was Stephen Holman, of Cannon Street, with

whom in 1867 the brothers formed a partnership to establish the branch house of

Tangye Brothers & Holman, with warehouse and drawing-office at 10 Laurence

Pountney Lane, not far from London Bridge. In accordance with the terms of the

agreement, Richard started work in the London office, thereby increasing his own

commercial experience and considerably extending Tangyes’ business connections. He

enjoyed these years in London ‘I have often felt since that that period of my life covered my happiest experience’.

The agreement was in form somewhat complex. Stephen Holman, himself an

engineer, had obtained a number of patents for various types of pump, which

Tangyes now undertook to make and to sell entirely through the London firm. In addition, Holman was already

agent for a number of other manufacturers, and these arrangements were to be

continued. The catalogue of 1870 — an excellent example of a comprehensive

trade list with engraved illustrations, descriptions and prices, well-printed

and bound — therefore covers not only the whole range of Tangye machines, but

also includes a number of products not made at Cornwall Works, such as portable

steam engines and locomotive traction engines. For their part Tangyes agreed

not to establish any similar business or concern, apart from one already in

existence at Newcastle-on-Tyne, nor to appoint any Agent or Agents in any new

district without the consent in writing first obtained’ of Stephen Holman. Such

a wide and unqualified clause answered well enough at first, but became

increasingly restrictive and irksome as trade continued to expand.

|

|

The Newcastle partnership of Tangye Brothers

& Rake, founded in the middle ‘sixties, enabled the firm to build up a

valuable trade in the important northern markets of Northumberland, Durham and North Yorkshire.

Upon the death of A. S. Rake a few years later, the branch continued to prosper

under the able management of George H. Haswell. In 1877 it became Tangye

Brothers, Newcastle.

In the similar industrial area of South Wales two partnerships were formed:

Tangye Brothers & Steel, Newport, and Tangye Brothers & Steel, Swansea.

Less fortunate than the northern venture, these branches ran into certain

administrative difficulties and the great trade depression at the end of the

‘seventies finally forced their dissolution. T. Dyne Steel, however, continued

to act as the firm’s agent for the area.

By

the mid-seventies Richard Tangye was determined to end the exclusive London

agency and to over-ride Stephen Holman’s veto, which he had chosen to exercise,

on the establishment of new branch houses. After several years of prosperous

and expanding trade, Tangye Brothers were at the time in a strong financial

position and in 1877 they opened two branch houses, one in Manchester the other in Glasgow.

The firm was thus represented in the four largest industrial areas outside the Midlands.

|

Tangye Brothers & Holman, of course, continued to be by far the most

important single selling channel, and the commercial prestige and convenience

of a London house constantly increased. It was not long before Richard began to think

Laurence Pountney Lane was

too small and out of the way for the display and sale of goods. The yard and

warehouse there served well enough and were retained but in 1878 a new block in

the recently-built Queen Victoria Street was acquired for the offices and showrooms.

In various speeches and writings, Richard was fond of illustrating his

conception of progress in the City of London by this example: ‘In London the

firm owns the large and handsome block of buildings (known as Cornwall House,

35 Queen Victoria Street), covering the whole of the site of Sir Christopher

Wren’s Church of St. Antholin, the bustle of their daily business contrasting

in marked manner with the deserted aspect of the old Church for many years

before its removal; the Sunday congregation having long been reduced to less

than a score’. Here the London House of Tangyes Ltd. remained until its own end

came rather more barbarically and certainly more suddenly in the air raid on the

eve of 1941. The Church of St. Antholin had,

after all, enjoyed a longer life than Cornwall House with all its bustle and

activity.

EUROPEAN TRADE

It was not merely fortuitous that Tangyes’ most rapid development coincided

with extremely favourable opportunities in overseas markets. Liberalism and

imperialism both contributed to the excellent trading atmosphere of these

mid-century years. The liberal policy of free trade had won many successes, of

which the commercial treaty with France, negotiated by Richard

Cobden, was an outstanding example.

In 1860 when the French Treaty came into force, Tangyes had just made the

acquaintance of Philippe Roux, a merchant trading with France and partner in a Birmingham agency.

One clause of the treaty particularly simplified the export of engineering

products:

‘The importer of machines or mechanical instruments, complete or in detached

pieces, of British manufacture, shall be exempt from the obligations of

producing at the French Customs any model or drawing of the imported article’.

Exports to France soon increased and at the same time a long-standing personal

friendship developed between the Tangye family and the family of Roux in Paris.

|

|

Philippe Roux undertook almost the whole responsibility for furthering the French

trade during the following decades. He equipped showrooms in the Place de Ia

République which were ‘magnificently laid out and managed and kept’. He also

opened sub-agencies throughout France

entirely at his own expense. At the time of the important Paris Exhibition of

1878 he took full charge of the arrangement and display of Tangye

products. The care which he took, coupled with the workmanship at Soho, was

rewarded by gold medals for engines, and for condenser and hydraulic jacks, a

silver medal for compound and special pumps, and a bronze medal for lathes.

The value and importance of Roux’s organization became particularly evident in

the mid-eighties when intense economic depression at home was partly mitigated

by an increased demand for Tangye products in France. Philippe Roux died in 1893:

to do him honour two of the younger generation, Lincoln Tangye and Harry

Tangye, attended the funeral in Paris of one ‘who for thirty years was so pleasantly associated with the Cornwall

Works to the great benefit of the general business’.

Roux’s Birmingham partner in the earliest days was H. L. Muller, who dealt with the German trade.

The rise of Prussia,

the creation of the German Empire, and the growth of German industry, made this

a more difficult market than the French. Towards the end of the ‘seventies,

however, Richard Tangye determined to break into it and discussed the

possibility of setting up a machinery depot in Berlin. The greatest drawback was the

impossibility of obtaining patent protection for British goods. In December

1877, Richard Tangye wrote to Muller in high indignation, after failing to

obtain protection for the ‘Soho’ engine: ‘We endeavoured to patent this engine

in Germany but the respectable German Government took our money

For

that object and then declined to grant the patent; a proceeding which we call

robbery, but which we presume they call providing for the military budget. Bad

success to the cause which requires to be supported by such means. (You will

think this coming down hot upon Fatherland, but it is certainly deserved!)’

Other European markets presented difficulties for different reasons. In the

early years the Holrnan partnership agreement prevented Tangyes from giving

exclusive agencies for particular areas, such as that sought by a Mr. Reska

travelling in Austria.

Where possible, however, special terms were allowed, to merchants like F. W.

Petersen & Co. of Copenhagen, who undertook the Scandinavian markets. This

particular agreement excluded the Russian trade where irregularity of payments

by St. Petersburg importers created special problems. During the ‘seventies, attempts

were also made to capture the southern European trade and agents were appointed in Turin.

In 1881 James Bache was appointed Tangye agent in Spain.

The following decade was one of acute commercial depression and little progress

was possible. When trade revived the newly developed gas and oil engines helped

to extend European interest in Tangye products. Branches were established for

short periods at Genoa and Bilbao. George Haswell, now transferred from

Newcastle to Cornwall Works, made many useful commercial

acquaintances on long journeys through Scandinavia, Russia and Turkey. But

when Haswell visited Constantinople in 1895, he arrived in the wake of ‘a terrible massacre’.

In less than twenty years the troubled Balkans were to upset irrevocably the nineteenth

century European scene.

|

EMPIRE TRADE

For British industry ‘trading under the flag’ played a vital part in its

success. This was the age when expansion in Australia, New Zealand, North America,

and later South Africa opened up enormous, and entirely untouched, markets.

The discovery of gold added to the excitement and increased the attractions

of these countries as potential buyers.

Richard and George soon felt the fascination, and both travelled to Australia and

New Zealand on several occasions.

In October 1873, George Tangye, in writing to his bank, said: ‘It is intended

that the writer Mr. George Tangye and his brother-in-law, Mr. Robert Price,

will proceed to Australia in the S.S. Great Britainwhich leaves Liverpool on the 25th inst.

From Australia they go via New Zealand, San Francisco, and New York to England in the autumn of next

year’.

A few months after George’s return, Richard set off on a similar trip. On his

way back he arrived at San Francisco in March 1876, and George immediately set off to

join him in America. They met in Niagara and travelled home together. As a result of

Richard’s visit to Australia agents were soon appointed at Melbourne and Sydney.

W. B. Jones at Melbourne was offered

very favourable terms to help him to become established. His position was

particularly advantageous, for he owned a bonded store which enabled him to

build up stocks without paying duty until he actually sold the goods. In Sydney, Messrs. Blacket

& Davy, described by Richard in 1878 as ‘most respectable young men . . . thoroughly trusted by us’

undertook the agency. The name of Tangye was not

altogether unknown in the continent for orders had already been executed for

the South Australian Government and other customers. The agents were to be

responsible for furthering and increasing the trade wherever possible.

Successes at the Sydney and Melbourne Exhibitions of 1880 and 1890 provided

valuable advertisement. At Sydney the firm won nine medals and several first prizes, but from

all we hear, obtained the best prize of all in the shape of some very large orders.

Richard and George stood firmly by the Australian trade and its somewhat

unusual conditions and in a few years the agencies were replaced by branch

houses at Melbourne and Sydney. But it was not easy to sell in Australian markets

on orthodox lines. To attract customers it was essential to carry large

stocks on the spot; money came into circulation unevenly throughout the year,

for it was plentiful after the annual wool sales but scarce in the preceding

months and this made necessary the conduct of business by bills more frequently

than was normally justifiable at home. Payment by instalments was also a usual

practice. This in its turn led to difficulties during unfavourable climatic

conditions which sometimes persisted over several years. Despite repeated

explanations by Richard and George to their fellow directors and further

Australian visits, these problems caused consternation at home among those

members of the firm used to ‘sound finance’ and short-term credit.

Although the branches survived the depression of the ‘eighties, continued

drought and other economic difficulties eventually made it impossible to

continue. Tangyes closed the Melbourne branch in 1894 and the Sydney

branch in 1896. The agency for the whole continent was then successfully taken

over by Bennie, Teare & Co.

The New Zealand trade was at first organized from the Sydney branch, which in

November 1892 made an arrangement with John Chambers & Son, of Auckland, to

act as the sole vendors of Tangye products in New Zealand and to undertake all

the travelling and advertising in the islands. This system, however, led to duty

being paid twice on each article. Moreover, communications were poor between

the two countries so that time was wasted in fulfilling orders. Like Australia

, subject to agricultural fluctuations, the New Zealand trade at

first only added to the financial difficulties of the Sydney branch. In November 1893, therefore,

Tangyes Ltd. made an agreement directly with John Chambers & Son for them

to act as Tangye agents throughout New Zealand. John Chambers, before

emigrating in the ‘sixties, had taken part in the building of the Great

Eastern. His son, J. R. Chambers, also an engineer, had spent two years at

Cornwall Works as part of his training, and his knowledge of Tangye machines

and business methods was of considerable value.

At first, delays involved in ordering half-way round the world, securing

payment in an under-capitalized community, and remitting regular sums to

England, caused some doubt of Chambers’ financial acumen among the older

members of the Tangye board. The Sydney already put forward by the foremen a few years’ earlier. It was designed to

reduce administrative costs and to make possible one standard of benefit; the

firm acted as treasurer, and a committee was appointed to represent the men of

the various departments. George Tangye became first President, and George

Deakin, one of the senior foremen, Vice-President.

In addition to sickness and funeral benefits all members of the Provident

Society automatically came within the provisions of the Accident Fund. This

Fund was Tangyes response to the Employers’ Liability Act of ‘88°; they wished

to tie in their new responsibility with the other welfare schemes. Much

attention had already been devoted to safety and accident prevention in the

Works and the firm felt they could go further than their legal liability by

agreeing to pay compensation even when the injured man might have contributed

to the accident. Similarly in the case of accidental death, whatever the cause,

benefit would be paid to the dependents. Introducing the Fund, Richard Tangye

named two conditions: first, ‘you must be

a member of a provident society, because we act on this principle, that we do

not help those who will not help themselves’, secondly, ‘the money will be paid in any case, but if

you accept our proposal it will be only reasonable that we shall be exempted

from any further liability’.

FOREMEN’S TRUST

As the firm grew in size and complexity, Tangyes developed a system of suitable

incentives and rewards for senior men whose continuous service over long

periods was considered to be of first-rate importance. Many of the foremen of

the ‘seventies and ‘eighties had begun work at the bench or in the workshop

alongside the brothers. It was natural that they should be regarded, therefore,

rather as lieutenants of the management than as representatives of the men.

Instituting the new Foremen’s Trust Fund in 1878 Richard Tangye explained that

in his view ‘a foreman ought to be entirely independent of the men under his

superintendence and not subject to be censored at a trade union meeting by the

men under his control for anything he had done in the exercise of his duty to

the firm’. For this reason any foreman who should in the future join a trade

union would be excluded from the benefits of the Fund. The Fund provided for

payment of a sum of money to dependents of a foreman who died while in the

company’s service, or for weekly payments to a foreman absent through illness.

Of seventeen foremen listed in 1876 eight had been first employed with the firm

before 186o. All were tried and trusted men to whom was delegated considerable

authority and responsibility in running their various departments. George

Tangye, for instance, instructed Henry Guy when he was promoted to foreman in

1872: ‘you will have full power to employ or discharge the hands inside the

large fitting shop doors with the sanction of the office in case of appeal’.

The foremen were also consulted in matters of welfare like the Dispensary

scheme, and they organized the Hospital Saturday collections and Charity

Concerts. The names of many of the foremen appear, also, on the lists of

patents taken out or used by the firm. The foremen were often able to see where

the efficiency of existing products could be increased and many of their

patents are for such improvements.

Throughout the Works, family names constantly recur over the years, and

sometime in the ‘seventies, to mark the loyal service of so many, the firm

instituted the award of silver medals. They were presented to men like James

Hughes, who joined the brothers in January 1858, and was later foreman smith;

Alfred Teague, a foreman pattern maker, first employed in January 1859, and

whose son was already filling an important post in 1878; George Deakin, who

came in February 1859, was a tester in 1869, foreman of the jack shop in 1876,

and still at work in 1895 although his poor state of health at that time caused

the Board of Directors to seek a gradual and honourable form of retirement for

him; Henry Guy, the first workman at Mount Street, of whom George Tangye later

wrote: ‘He remained with us for over

thirty years, until his death. He was a splendid and faithful workman, and he

was honoured by all who knew him’.

CORNISHMEN

All the lists of names which have survived bear reminders of the presence of

Cornishmen — Tredinnick in the foundry, Treglown the engineer, Teague,

Tregenna. From the first a close association was maintained with the Duchy,

local Cornish newspapers frequently carried news about the firm, and, as the

depression in tin mining increased, more and more workers were recruited for

the Cornwall Works. In September 1877, George Tangye who was visiting Cornwall, received a

letter from J. T. Andrews, the office manager, enquiring about brass-casters:

‘Will it be possible to get one or two men from the Perran Foundry to come up

here?’ At the end of Whitsun week a year later Richard Tangye was told that a

good few of the employees were ‘coming home by excursion today from Cornwall’.

By 1905 there were so many Cornish emigres in Birmingham that they formed a

Cornish Association with Richard Tangye as first President.

At the inaugural dinner he claimed that he had been instrumental in bringing

more Cornishmen to Birmingham than any other man and added ‘with scarcely an

exception they have been a credit to their county’.

APPRENTICES

In the earliest years at Cornwall Works, Tangyes seem to have provided a

general engineering training for ‘gentlemen apprentices’. In 1878 Richard

Tangye wrote ‘Some years ago we were in

the habit of taking young gentlemen to go through all departments, and received

large premiums with them, but they were an unmitigated nuisance, disorderly and

not answerable to discipline, so that we made a resolution to have no more and

have always been glad of it’. One or two indentures were sealed during the

next few years, a subscription of £10

to the Works Library being substituted for a premium, but evidently

they were no more successful, for in 1885

Richard Tangye reiterated the decision not to take articled pupils.

The organization of the Works on a strictly departmental basis, each shop under

its own foreman responsible only to the management, had in any case made the

co-ordination of training in different fields almost impossible. Each

department continued to attract apprentices bound only to a particular trade —

a training of which Richard Tangye wrote: ‘it is good only for sons of workmen,

who for the most part only expect to be foremen of their particular branch of

the trade’. On this craftsmanship in the shops, however, the firm’s

long-standing reputation for fine workmanship and high standards has always

rested. Very many of the leading engineers of later years obtained their early

training at Cornwall Works.

BEYOND THE CORNWALL WORKS

The liberal and philanthropic efforts of the brothers were not confined to

their own workpeople. For many years Richard Tangye played an active part in

local politics. He served for a few years on Birmingham City Council and also

sat on the Smethwick School Board. Opening new Board schools near the Works in

1883, he made some interesting comments on the educational system:

‘Since the passing of the Education Act more than one thousand Board School

Boys have found employment in the Cornwall Works, and the universal testimony

concerning them is, that as compared with those of the era previous to the

existence of the Board Schools, there is a most marked improvement in every

way. The lads are more orderly, more amenable to discipline, and much more

intelligent; they show a great eagerness to learn the business of their lives,

and as a natural consequence they master it much more thoroughly and in

considerably less time.’

Richard Tangye’s insistence upon the importance of

scientific and technical education on the same occasion — ‘absolutely essential

if this country is to hold its own’ — has a strangely familiar ring today.

The two brothers jointly presented Birmingham with a valuable contribution towards

the new City Art Gallery. In 1878 they offered £5,000 towards

the purchase of works of art for the City on condition that the Corporation

would undertake to build a permanent Art Gallery.

They also agreed to give a further £5,000 if an equal sum could be raised by

donations. The conditions were fulfilled and the brothers finally contributed

£11,000 with the declared object of

improving taste and artistic standards throughout the City.

For his many services to his adopted city, especially in the cause of art

education, Richard Tangye was knighted in 1894.

George Tangye, never an active politician, served the community in different

ways. He was losely associated over many years with the General Hospital and

Sir Josiah Mason’s Orphanage. For a long period he sat as a Birmingham City Magistrate. For over forty years George

Tangye lived at Heathfield Hall, James Watt’s old home, which still contained

his garret workshop in its original state. His interest in Boulton and Watt,

stimulated in his boyhood days, was life-long. Perhaps his most munificent gift

after the Art Gallery donation was the Boulton and Watt Collection, presented

to the City Reference Library in 1911.

It now forms a valuable section for historical research. Watt had brought

the steam engine to Cornwall: in some measure George Tangye paid tribute by

presenting the Watt memorials to their adopted town.

1913 STRIKE

As in international affairs signs of unrest began to show themselves

before the First World War, so in labour relations there was an increasing

sense of change. The National Insurance Act of 1911 and other legislation of the 1906

Liberal government was laying the foundations of a Welfare

State in which there would be far less opportunity for philanthropy. Among the

workers, trade union organization especially in unskilled trades, was becoming

rapidly more effective.

As a result of this trade union development, Tangyes Ltd. in 1913 suffered one of their few

strikes. The Workers’ Union had greatly expanded during the two previous years,

especially in the engineering and allied trades, and eventually put forward two

demands; first for a basic minimum wage of 23/- for all adult male workers, secondly for recognition

of the union. The struggle began at Tangye’s on 18th February, 1913. By the end of the month,

1,600 workers were on strike. Tangye’s then offered the 23/- basic wage and on 3rd March the men returned to work.

As on previous occasions Tangye’s led the way for other employers but elsewhere

the claims were not won so easily. The Black Country Strike, as it became

known, lasted in many places until July 1913.

The advent of the Welfare State and the increasing power of the

unions heralds a new phase of industrial relationships which, affected by wars

and depressions, is only bearing its full fruit today.